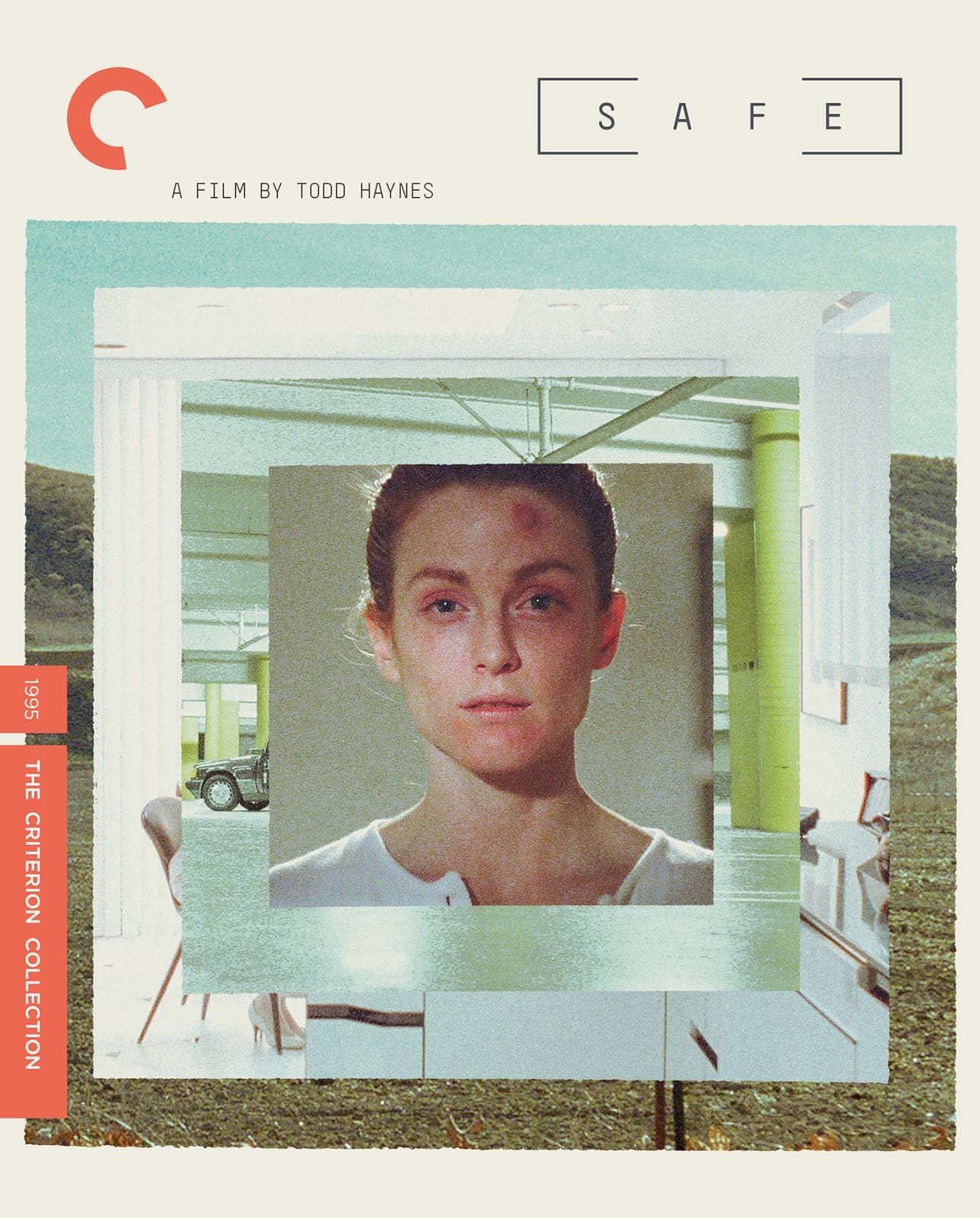

#1: Safe (1995) (dir. Todd Haynes)

The random number generator chose Todd Haynes’ Safe, a film I have seen many times. It still haunts me in ways that very few films of the past can so it's a great place to begin this endeavor.

For the first edition of “Five Years,” the number generator chose Todd Haynes’ Safe, a film I have seen many times. Watched it with my morning coffee - I’ll revise an older review I wrote and include some new thoughts and it will be the first of 260 pieces. This kicks off the 5-Years Project so welcome one and all.

The first couple of times I watched Safe, I mainly viewed it through the prism of suburban malaise and a sense of imprisonment especially in terms of what it means to be a housewife. This is a film that’s also in conversation with Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Safe warrants multiple interpretations due to its ambiguous nature especially in terms of how it concludes. After a half dozen viewings, it’s safe to say that it’s reductive to proclaim that Safe is just about environmental illness or materialism. That would be like saying that Martha Marcy May Marlene is just about cults.

In some way, the character of Carol in Safe is about to become Martha Marcy May Marlene at the end of this movie - someone who never felt they belonged now feels they might but is it a good thing? Both films seem to scream out with existential terror that the lack of identity is not only anxiety-inducing but potentially inevitable due to the societal structures we are forced to accept as “normal.” (Read into this in any way that you will - some will look at this film from a queer perspective and that seems apt as well). We become shaped and shifted by different forces and stimuli, due to vulnerability, openness, mental instability… any number of factors. Our true self is bound to get lost and possibly evolve or devolve. This is one of those films that I need to proceed with caution with because it can easily be a long-winded essay that goes completely awry to where I am probably going to adopt a less-is-more type of analysis rather than deep diving into every facet that I find interesting.

Safe seems to also be a precursor of one of my favorite TV shows, The Leftovers, in which the decline of personal “faith” and “family” and “connectedness” is a result of trauma, something I relate to. After experiencing near-death at a young age, the death of my closest family member years later, and a number of illnesses, I should not beat myself up for the awkwardness I feel in the real world because sometimes I feel like a floating ghost. Other times I feel more alive than words can describe, and sometimes it's due to the experience of watching a movie like this one.

There are scenes in Safe that hit me harder than just about any movie ever made, particularly one where Carol starts crying for no reason when she returns back to her cabin, which mirrors the scene that made Punch-Drunk Love my 2nd favorite PTA movie oddly enough. Trauma and uncertainty make you feel like a non-person, and Safe captures a number of feelings: depression, anxiety, isolation, fear, complacence. It even traps Carol inside patriarchy both with the cold post-credits sex scene and the cold lack of compassion from her husband who is tired of hearing about her “headaches.”

I can understand being turned off by the experience of Safe. At times, it’s detached, distant. Probably because we are experiencing Carol’s inner world and confused state. Look closer for Haynes’ compassion and warmth such as the new friend that visits Carol after she has her crying spell during her first night at Wrenwood. Haynes emphasizes Carol's alienation by using long shots when filming Carol inside the house; the enormous rooms make her seem even smaller, and Haynes typically includes the ceilings of the rooms within the frame in order to give the viewer the sense that Carol is trapped.

Carol gradually becomes nothing more than a ghostly presence in the house, which is illustrated by several haunting scenes in which Carol sleepwalks around the house at night (incorporating one of my favorite Brian Eno instrumentals at one point). Again, she feels an apparition imposter syndrome. “Why am I here?” The film certainly is critical of institutions that try to pigeonhole you or say, “This is what’s wrong with you,” so Wrenwood could certainly be any number of things: psychiatry, politics, religion, gender. That’s the power of Haynes’ work here.

"Is this the same story as White Noise, only a million times better as a film?" - Katie Jefferis

He inserts little hints about yellow wallpaper, AIDS, psychosomatic disorder, what her friend’s brother might have been. But it’s never explicit, unlike something like American Beauty which outright tells you something like “This is not a marriage! We’re not happy! This is just a couch!” Attempts to retreat into any institution might be soul-crushing and toxic to one’s identity. Some people might feel that way about marriage, some might feel that way about sexuality/gender, some people might feel that way about religion. I think the scariest part of this film is the idea that identity is potentially fluid to a fault. We can never fully be one thing.

Our bodies won’t allow it due to the decline of cognitive processes or the failures of the human immune system. Even the person we think we are can be destined to be deconstructed and reconstructed at any given point due to factors that are often out of our control. Maybe we need to accept this rather than fight it by trying to fit in to society. Yet we are drawn towards community, unity, and feeling connected through a shared experience. This is why support groups exist and that’s ultimately where Carol finds solace. Haynes brilliantly showcases the idea of AA as being “questionable” through dialogue early on in a locker room, then mirrored later through an actual support group that Carol attends.

In the end, there are no easy answers. This is also a film that I wouldn’t write about its narrative or plotline necessarily because it’s more about the feelings that are conjured up while experiencing this story. And those are the ones that become my all-time favorites. The ones that explore our psyche in a way that doesn’t piece things together easily. That’s what memory feels like. We might be plagued forever by our trauma. Carol’s downfall might be easily succumbing to something in hopes of it making the most sense in her life. But isn’t this what we all do whether with a hobby or by falling in love?

I think there’s a lot to gain from the experience of watching this movie more and more, and I think the support group scene says a lot about our varying reactions to trauma or “sickness.” And there will always be someone who thinks they have the right to lead a group and say what they think is the cause of one’s personal pain. I feel Carol’s pain, but I’m also angered at her blind ignorance. For some reason, that conflict inside of me is fascinating to revisit and I get more out of watching Safe for the tenth time than I did out of any philosophy class I ever took. Not to mention moments throughout this film being precisely what it feels like to have a panic attack.

Another scene I go back to is when Wrenwood leader Peter Dunning seems to blame illness on the fact that the afflicted have brought it on themselves. One woman seems to hold resentment towards this idea - external factors are believed to be the cause, not internal ones. Peter seems to think that once someone comes to terms with their past actions or transgressions, that is a vital first step to healing. “You let yourself get sick,” he says. This makes me wonder about the ultimate cause of environmental illness then. Is he essentially trying to say, “it’s all our fault that the environment is turning against us?” Perhaps leading to a commentary about global warming to some extent making this even more of a prescient film. Not to mention the fact that a rewatch today feels surreal given the recent pandemic we’re all fighting through. There were several reevaluations of this film early on during lockdown that brought up this point including several shots of those wearing face masks in public.

Try to let the mysterious elements of Haynes’ psyche and incredible talent as a storyteller here infuse you. A proper follow-up viewing to this might even be his recent courtroom procedural, Dark Water, another stark commentary on the way we are entrapped by capitalist ideologies who are poisoning the environment. I always think of Safe as a marriage of all the things I love from many creative artists I’ve revered: a little Pynchon-paranoia accompanied with DeLilo’s worldview filtered through a queer voice akin to Chantal Akerman.

It’s easy to see that Julianne Moore gives one of the best performances ever but notice the many nuances throughout. I would say that her speech towards the end, might be one of my favorite moments in acting history because it’s awkward, stilted and not showy in ways a monologue usually tends to be (kind of an inverse of Michael Shannon’s speech in Take Shelter). I’m not sure which critic said Safe was the best film of the 90s, but they may have been right. Emotional connection is what I live for, both in movies and in general. Safe is kind of the epitome of that connective experience for me that continues to grow with me as I continue to grow old and concerned not just for my health but for my place in this fragile, fractured society.

Listen to myself and Sharon Gissy discuss this film at length in a recent podcast: https://www.directorsclubpodcast.com/episodes/toddhaynes2