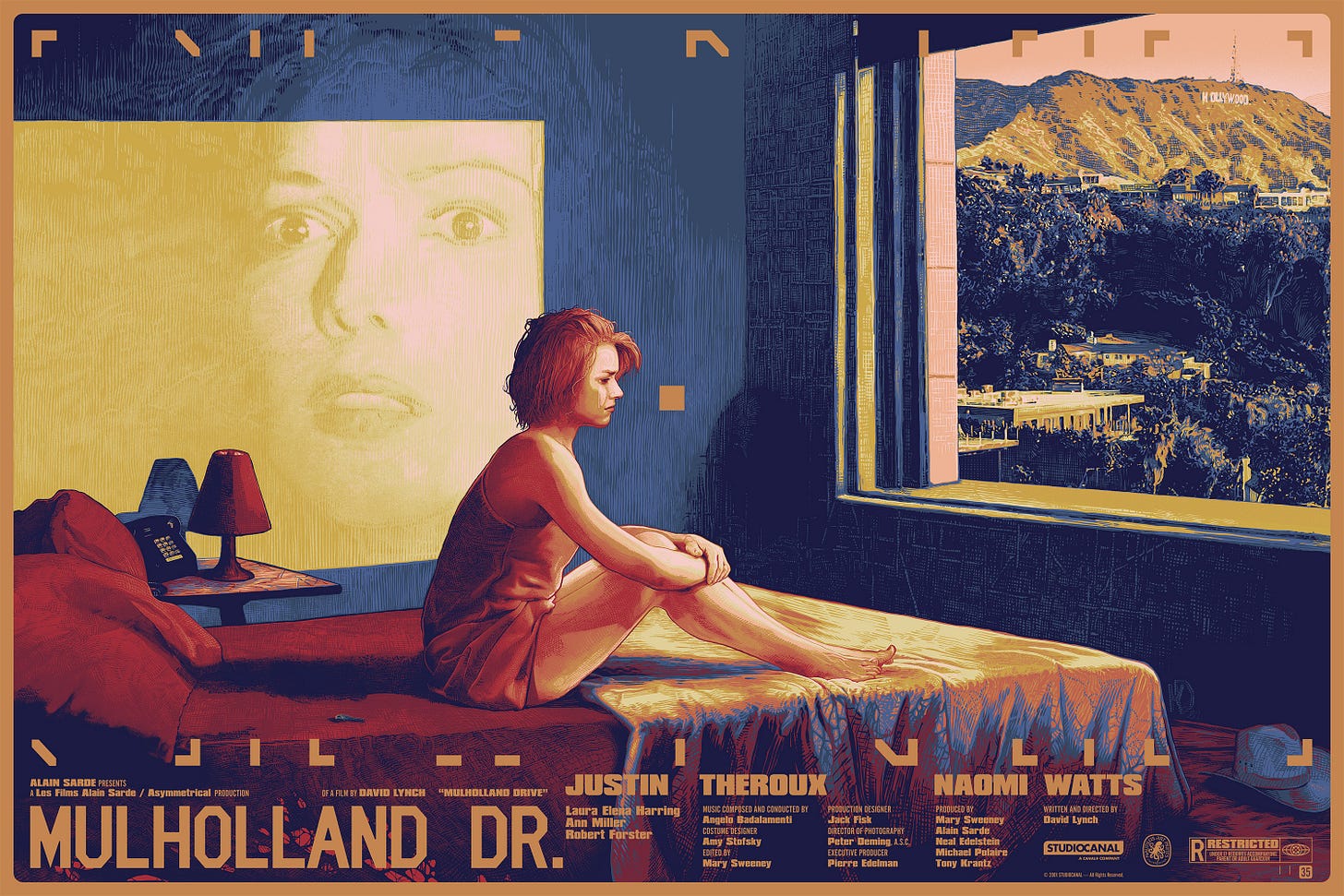

Mulholland Drive (2001) (dir. David Lynch)

This is the film. It is my favorite of all time. Thank you David Lynch for making it.

It was October 6th, 2001. My father was dying from cancer and my internal voice kept repeating, “Do not go to Chicago for the film festival premieres of Mulholland Drive and Waking Life.” My dad was in and out of consciousness due to the amount of morphine they provided at Hospice. Still, the nurses there seemed confident he would have at least another week.

My dad and I had short meaningful conversations here and there and of course, he remembered that I had tickets to the festival. Going home to sleep and leaving him was hard enough, but the idea of venturing out to see two movies with the possibility of my dad passing away at any time, there was no way I was about to take that risk.

That is until my dad told me, “I want you to go to the movies. Get away, enjoy yourself. I’ll still be here.” Of course, I was conflicted but I also had been there for several days watching over him, reading, talking with people we hadn’t seen in years. Playing the piano in the hallway. Everyone reassured me that if anything happened, they would call me immediately. During the drive in and even just sitting down to watch two movies back to back filled me with apprehension. How could I actually enjoy these films with what was happening to the most important person in my life?

The truth is, I didn’t entirely love Mulholland Drive in 2001 at that premiere. Perhaps my mind was elsewhere (duh). I wasn’t emotionally ready, especially since I had sat through Waking Life first which has many deep, unwieldy conversations about death and dreaming. That movie floored me to no end, having just taken an existentialist philosophy class and recognizing a lot of the ideas and even some of the lecturers discussing things I had a huge interest in. Those are my kinds of conversations and though I see why people don’t vibe with it, I certainly did.

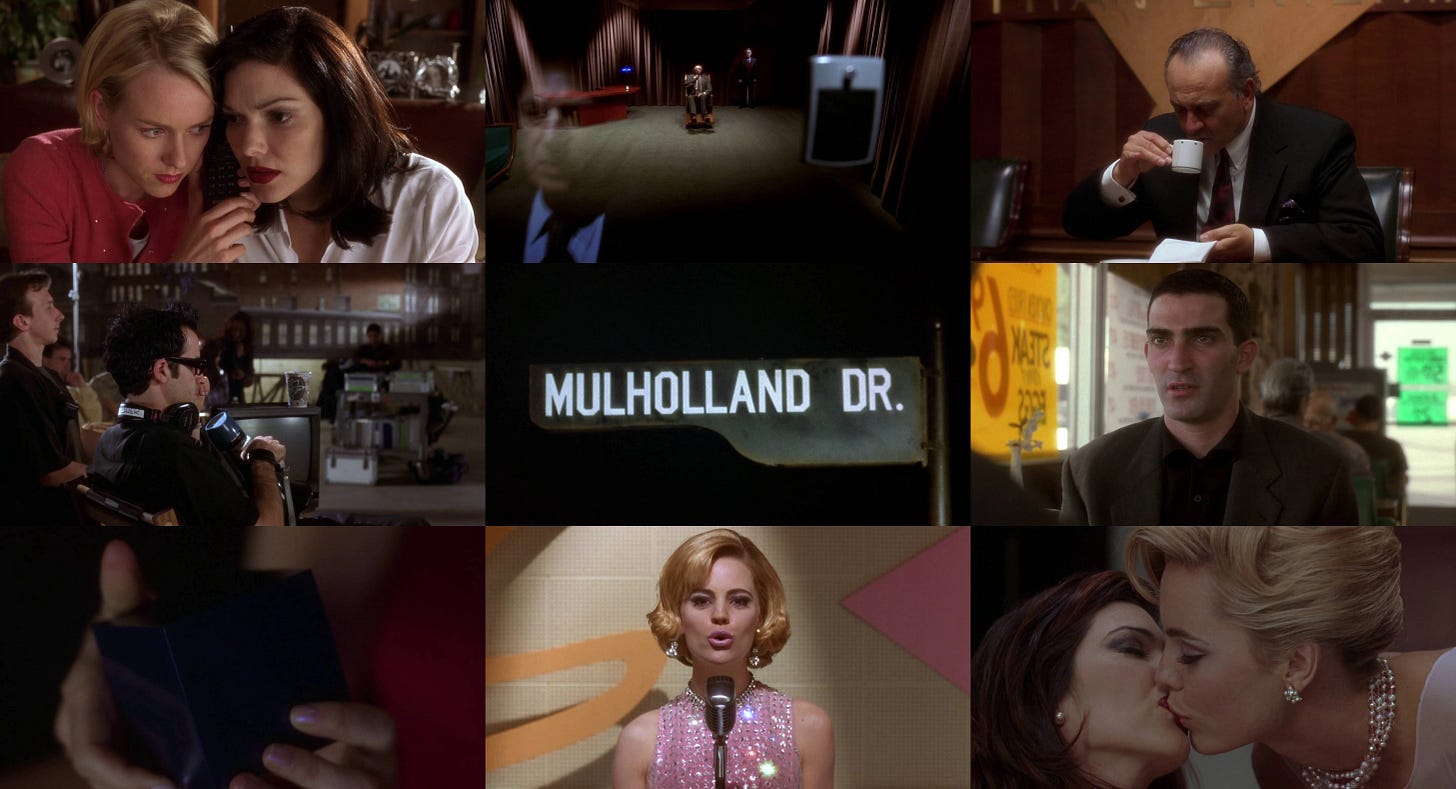

Then came the latest from David Lynch, my second favorite filmmaker of all time, someone I had revered as a result of seeing everything he’s done. Aside from making a mental note of how much I loved Naomi Watts’ performance and especially the Winkie’s diner scene, for some reason, it wasn’t until 15 years later that I finally fell in love with what would become my all-time favorite film. It has been at the top spot for a while now. It won’t change. Having seen it on the big screen four times now, there’s no greater experience for me than watching this film.

I’m not prepared to talk about the work of David Lynch as a whole yet since I’m writing this on the day of his passing. It’s a devastating time. I could go into more specifics and details about certain imagery for sure but that’s not what’s on my mind. I am thinking about L.A and the homes burned to the ground. I am thinking about the inauguration coming up in a matter of days. The last thing I needed to hear: that one of my favorite filmmakers left us. How could I not channel my gratitude to him for making my favorite film of all time. This is a loss that did make me cry.

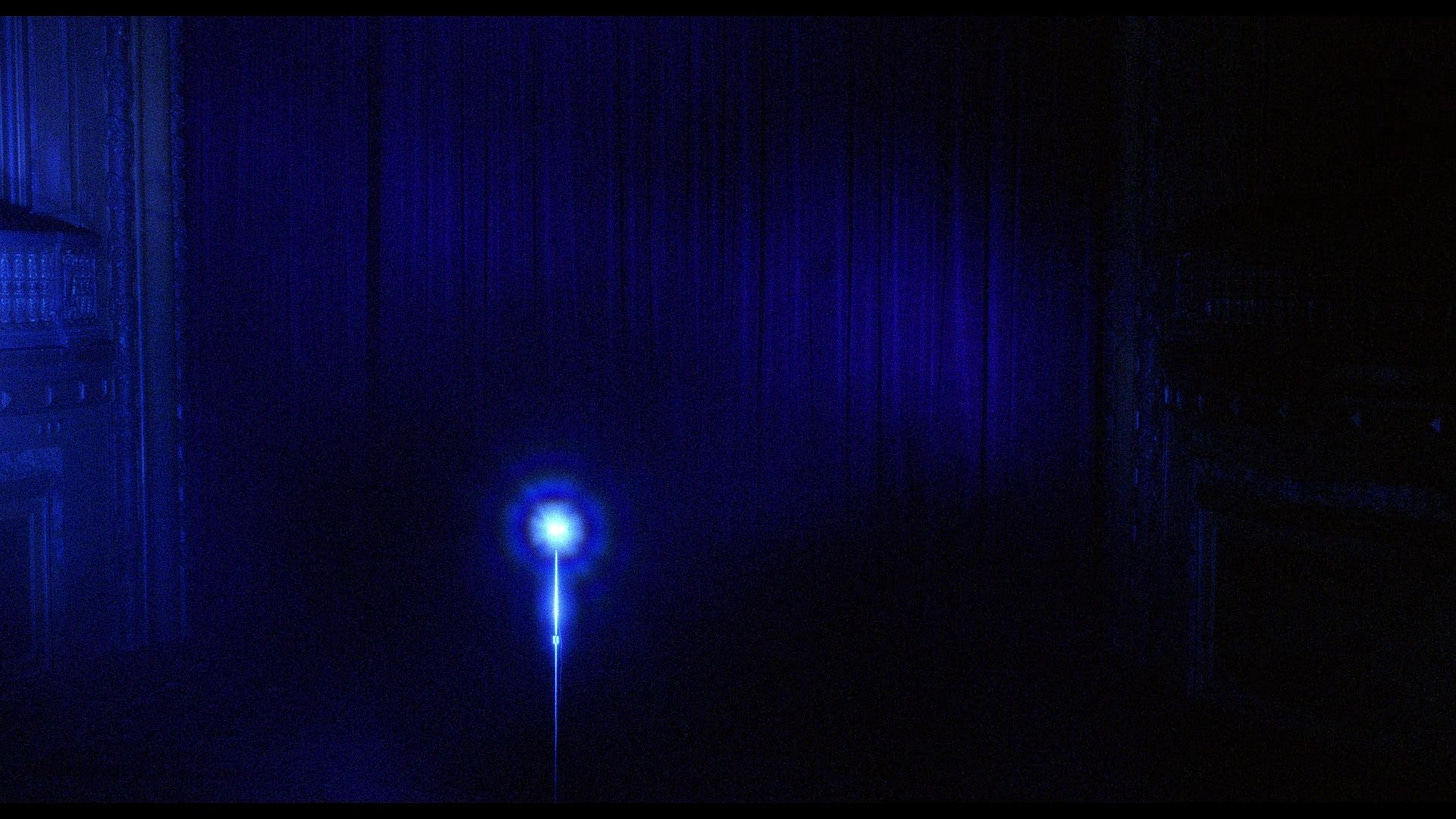

Perhaps I’m ready to dive deep into what makes Mulholland Drive his masterpiece and a huge reason why movies became my favorite form of artistic expression. I guess when I watched it for the third time a decade and a half after the premiere, I really wasn’t ready for my reaction to the Silencio sequence. I began to cry harder than I ever have at any movie before because I thought of my dad’s love of Roy Orbison, and the fact that he died the very next day that I first saw Mulholland Drive. I also was in love with the wrong person at the time of that third viewing. That may have had something to do with my reaction to that film and declaring it my favorite. Come to think of it, this may have been almost exactly a decade ago back in 2015.

I wouldn’t have even gone to see it had my dad not said it was okay and that he would hold on. Not only that, I thought of the love I had for others that was never meant to manifest fully including the current one I was enmeshed with. When something didn’t work out the way I had wanted to in my mind (or in my dreams), suicidal ideation was inevitable. Those screams at the end of this movie, I’ve done that both on the inside and into a pillow at the worst times in life.

This TV pilot turned film is not just about unrequited love and the broken dreams of pursuing a career in Hollywood as well as losing your mind to the point of suicide, it’s about reality being a living, breathing nightmare. Why else do we choose to escape into other worlds whether they exist when we sleep or we venture out to the local movie theater for a chance to forget how painful it is to be alive.

Mulholland Drive is a fully realized dreamscape nearly unparalleled in modern filmmaking beckoning us into a world that blurs fantasy and reality until the edges of both fade away completely. It contains a story of aspiration stolen by reality—a tale where ambition crumbles under the weight of actual pain and loneliness. And through this, Lynch gives us an almost unflinching portrait of identity splintered and scattered across existential terror.

Where fear attaches to something specific, anxiety reflects on the nothingness—the void. Think about Diane’s trajectory. Her life is shaped by choices that haunt her, by a depression that emerges from a confrontation with possibility and passion unfulfilled. Betty, the idealized dreamer, represents what Diane wishes to be but knows she is not. This is why there are constant interruptions even in an idealistic interpretation of events taking place in her psyche.

As the narrative unfurls, you feel an emotional undercurrent taking hold. Betty is an echo of hope diminishing into the shadows of Diane’s despair, her sense of self disintegrating before us. What Lynch does so effectively here is intertwine Diane’s unraveling with Hollywood’s broader promises—the glittery mirage of success and stardom held up as “The Dream” but perpetually out of reach for someone like Diane.

The city’s (dis)illusion of opportunity becomes her personal torment, and through Lynch’s layered storytelling, we see that tension play out as both psychological and cultural critique. Most folks get caught up in the puzzle-box element and rightfully so, but instead of contemplating what everything means, I go right to the feelings conjured up as a result of experiencing this true blue work of art.

Take the scene at Camilla and Adam’s engagement party, for instance. It’s not merely an autobiographical snapshot of Diane’s heartbreak; it’s a moment drenched in the tangible collapse of romantic connection. The Diane we encounter here is awash in disenchantment, her body language sinking with each passive-aggressive humiliation. Her torment is clear. The abrupt cut from that dinner into the diner is one of the very best in the film.

Lynch’s idea of despair finds a visual manifestation—not despair as dramatic suffering, but as an ongoing failure to reconcile herself with the outside world as it truly is. This identity collapse is woven throughout Diane’s mental undoing carried by a profound guilt over Camilla’s death, her inability to embrace her failures, and her attempt to hide behind fantasies like Betty, where she controls her narrative, if only briefly. I’m sure many of us can relate to wanting to hide behind fantasies whether it’s projected onto a screen as entertainment or internally in our minds, when we think of a desirable encounter with someone while masturbating.

Add to this Lynch’s surrealist elements—the vagrant behind the diner, the smoky, ominous Club Silencio—and these images feel like manifestations of her guilt bleeding into every inch of her subconscious, heightening the dissonance between idealism and reality. And here we arrive at what truly drives Lynch’s narrative force: Betty and Diane embody the eternal human struggle between how we perceive ourselves, or wish to be perceived, and the stark truths we carry in quieter moments. It’s so easy to lie to ourselves, it’s harder to accept the consequences, the loss. This makes Diane relatable especially as someone who has experienced tremendous loss - both in romantic love and with the passing of a parent.

She mirrors our universal fears and unrelenting sexual urges—and the possibility that we’ll be undone not by external forces, but by the fault lines within ourselves. The mental collapse brought on by having to suffer alone, unable to let go. Placing Diane’s arc within broader frameworks of identity and alienation only deepens the tragedy Lynch examines—a tragedy not just personal to Diane, but reflective of Hollywood’s systemic illusions and inevitable betrayals. It’s Lynch’s take on how things haven’t changed much since Billy Wilder tackled similar ground with Sunset Boulevard.

In this way, Mulholland Drive is not only a surrealist exploration of personal anguish but also a scathing critique of the mechanisms that create, promise and then shatter dreams. Dreams that can create works or art or lead to us want to experience true love with another human being. Lynch found correlations and a recognizable dichotomy throughout his entire career. He knew that within this wide array of human experience exists both Bob and Laura Palmer. Good cannot exist without evil. So how do we live with that? Perhaps by finding love. Love that won’t leave.

The tragedy here lies not in fleeting fame and lust but in unfulfilled potential. Diane doesn’t fall from the heights of stardom—she never truly ascends or gets to experience a long-term connection with Camilla. Her dreams crumble even before they’ve had a chance to fully materialize. And this deepens the stakes. Diane is not merely consumed by Hollywood but is ground down by its systemic indifference, where even the promise of opportunity for love and success are rendered as unattainable, an illusion. There is no band. There is no Betty. There is no Rita. This film is a recording.

There are a lot of moments that I could parse as favorite scenes all by themselves. The cowboy meeting, the Winkie’s diner sequence, the dinner / marriage proposal, the final primal scream from Diane (something we would also see again at the end of his final work, Twin Peaks: The Return). To quote Sutter Cane from In The Mouth of Madness, “did I ever tell you that my favorite color is blue?”

Blue is often thought to represent a calm and clear reflection that leads to truth. Anytime the color blue appears, it is Diane confronting hurtful honesty. The closer Betty gets to harsh reality, even her blouse changes to a light blue. When they first get in bed together, even the sheets / pillow cases are a faded shade of blue. And of course, the best scene of all in Club Silencio, smoky bursts of blue appear throughout. Look at the establishing shot outside the club alone. Not to mention the box and the key. Lynch thought about these intricate details with a level of precision and attention that few others did. But it’s up to the audience to decide and interpret the meaning.

Think about the silent yet sinister presence of forces like the Castigliane brothers or the hitman or the memorably hilarious cowboy—they’re fragments of an imagination, sure, but they embody the machinery of exploitation that looms over every starry-eyed hopeful. Nearly every character embodies abstract dreamlike representations of madness. Adam Kesher represents the integrity of cinema who realizes that the only way to succeed is to compromise. Betty would’ve been perfect for the role in The Sylvia North Story when they make eye contact, but the powers that be are in control of important decisions.

In the idealized memoryscape of Betty, she begins as naive and optimistic. Her hopefulness and determination becomes truly magical during one of the greatest audition scenes ever committed to celluloid. It’s also a moment that basically says to the audience, “I am Naomi Watts, watch me give one of the greatest performances by any human being ever.” Sadly, this is the opposite of how it played out in reality when Diane relays to us at the dinner party, “Camilla got the part.” Resentment cuts deep.

David Lynch digs so deeply into the raw emotional truths we often try to bury away and escape from. He has with so many of his other films too but I’ll save thoughts on those for another write-up. Mulholland Drive is focused on unrequited love and/or a life unfulfilled—the ache of wanting, of yearning, of longing, just knowing in your whole being, that the one person your soul is woven into will never ever love you back. That's a wound that feels impossible to let go of. And this film, in all of its surreal chaos and dream-logic storytelling, somehow brings that pain to life with Diane/Betty, yes, but it transcends just her.

When I watch it, it feels as though Lynch reaches through Diane's story to pull at something deeply familiar in all of us. While it stokes the notion that reality can grind us down and isolate us, there’s also this sharp contrast—this notion of how dreams can become these euphoric, chaotic sanctuaries, even if they’re fleeting, even if they can’t save us entirely. Dreams, they offer us a glimpse into something better, don’t they? But does the cost of chasing dreams perhaps undo us in the end? Diane shouldn’t have pursued Camilla. Yet she couldn’t help herself. Impulses get the best of us. We want the wrong love sometimes.

The moment that embodies all of what I love about cinema for me is the Silencio sequence. I cry every time and now that we’ve lost David Lynch, I expect to even more. I will go on record to say that it’s my favorite scene in film history. It’s devastating because it doesn’t just represent the intersection of art and artifice, or love and the lack of reciprocation. It’s personal, it’s real though it’s also not. I feel the tears of Diane and Rita in my bones to where it’s a communal experience of me being there, with them. Not to mention the performance of Rebekah Del Rio and what that song means.

It takes me back to moments in my own life when I gave my whole soul to someone who could never see me the same way—and it reflects that deep, aching futility that Diane embodies so utterly. Not to mention the song itself is called “Crying.” How could I not cry? I certainly did as a child listening to Roy Orbison sing it. Diane cannot live with the regret, the torment of what she’s done, but even more so, she cannot face a world without the one thing—person—who gave her meaning. I understand it far too well. It’s one of many reasons this became a favorite film that I go back to every single year.

Dreams, music, art give us these fleeting escapes. Hollywood, embodied by the imperfections of human beings making decisions for the artist, promises that too, doesn’t it? It teases you in a sense, making you believe that ambition and talent will allow your dreams come true. But what does that cost you? What toll does it take when you pour every ounce of yourself into your love for someone, or even into the pursuit of art, or achievement, only to realize that it will never fulfill you as deeply as you envisioned?

It’s that passion, so consuming that it blinds you to everything else. Mulholland Drive captures all of this, plunges us into it, messily and beautifully. But every time I watch, there’s this clarity too—that in its chaos, in its disarray of identity and ambition and struggle, Lynch has created something deeply, masterfully resonant for me—and for anyone who’s ever burned with longing for another or for something greater than themselves.

This is the film for me. It has been for about ten years. Perhaps it’s imperfect due to the fact that yes, it started out as a TV pilot then clearly shifts into something else at the midway point. None of that matters. Let the magic unfold, immerse yourself inside and analyze the experience over time - share your feelings with anyone who’ll listen. Mulholland Drive embodies not just the dilemmas and contradictions of existence, but the intoxicating wonder of being vulnerable, the painful and the joyous, colliding and crashing together like blinding desire poured into vinegar.

It’s every bit of humanity boiled down into jagged fragments of longing and despair, yes, but of fleeting moments of something breathtaking too. What part of you gets revealed inside the illusions you carry—when you truly stop to think about them is something we may not be cognizant of, but it’s there. What we’ve lost, what we truly want, is always there. Try to hide all you want, the blue box won’t let you forget. It contains the truth. The person behind the diner is holding on to it too. Your mind is its own “blue box.”

Night terrors and waking up in the middle of the night epitomizes a prevalent anxiety of having to exist inside a complicated reality for me. People can be cruel. So my guard is always up. But film has always served as a way to process my emotions in a way that’s healthy. Lynch made great art that would inevitably leave you with questions that you couldn’t wait to think about and share with others.

Mulholland Drive won’t give you the answers as to how to cope with loss of love you thought was both true and eternal, but it holds up a mirror—not just to its own fragile, fragmented characters, but to you as a dreamer, as a person living in this complicated world. In this film, Lynch didn’t just give us a masterpiece with Mullholand Drive. He gave us a piece of ourselves. Not just here, but through Laura Palmer and many many other of his creations over the years. I can’t wait to revisit all of his work later this year.

I didn’t get to meet David Lynch at the premiere of Inland Empire at the Music Box Theatre, but knowing I was in the same room with him, drinking coffee he helped to create, still warms the soul. Not to mention that he is responsible for so many remarkable achievements that it’s hard to summarize at this point in time. Nearly every film he made has a special place in my heart.

There will be much more to say about a number of his works in the future. For now, Silencio. RIP to a true master of pure cinema. There was no one like him, there will never be another. Same holds true for my dad, who told me to go to this movie as he was dying, because he knew I needed to.

This is so beautiful Jim. Thank you for finding the strength to write it.